| Today's Hours | 8am – 10pm |

|---|

| Today's Hours | 8am – 10pm |

|---|

Thanks to your newly-awesome search skills, you can ask a database to return a manageable, on-topic list of search results. But just because you've got 30 articles instead of 5,000 doesn't mean that all of them are going to work for your paper! How do you figure out which of the articles you should actually read? We've arrived at step 4 of the research process: evaluating your results.

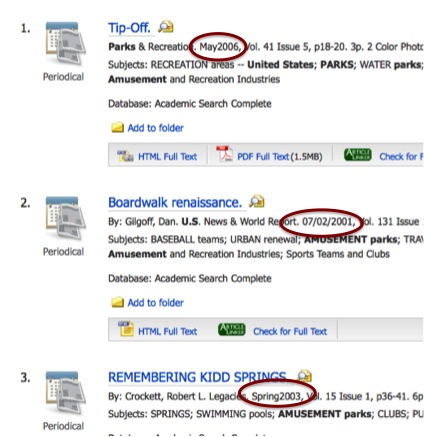

For the following examples, let's assume that you're working in Academic Search Premier. Note: when looking for the information described below, some of it will be available on the results page, while other pieces will require you to click on the article's link and view the detailed record.

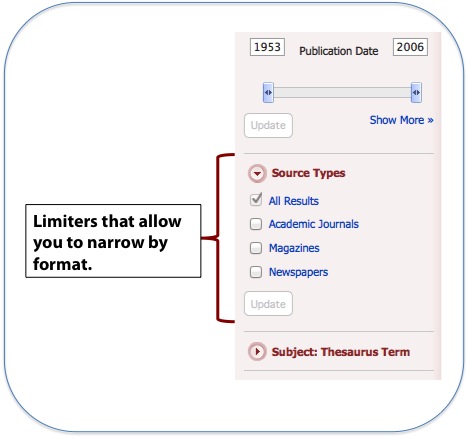

First, you need to figure out what kind of source you're actually looking at -- is the article from a scholarly journal, popular magazine, newspaper? It's not always possible to tell just by looking at the record, but you can use the Source Types limiter to narrow your results by format.

Any of the articles you find in a library database are trustworthy and okay to read, but you might have a preference for newspaper articles or be required to use scholarly sources for your paper. Make sure you know where your information is coming from before you read it!

If you're writing on a current event, you don't want articles written 10 years ago. If you want newspaper articles written during the 1970s Watergate scandal, you don't want articles dated 2010. If your topic has date limitations, make sure the articles you find are going to work for you.

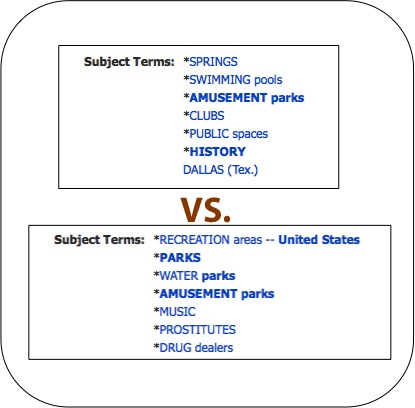

If we do a subject search for "amusement parks," every article in our results list will contain that subject label -- but it will have other labels, too. And subject labels are like tags, they describe ABOUTNESS, so looking at the labels will tell you something about its content! Look at the two examples below: just by scanning the subject labels, you can tell that these articles are about totally different things!

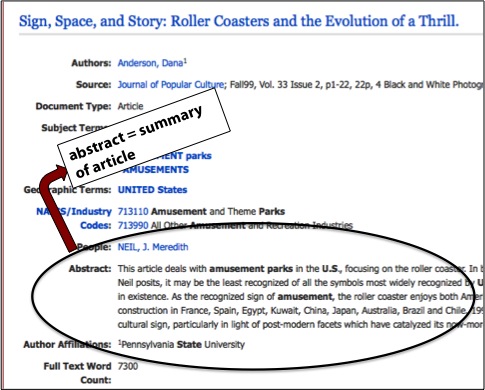

If you're very lucky, the article record will contain an abstract:

Think of an abstract like a movie preview or the back of a book: it summarizes the content of a resource so you can decide whether you want to watch or read it. Reading an abstract will tell you if the article is truly on-topic and useful for your research assignment.

(This sounds mildly insulting, but bear with us.) Because scholarly journals are written by professionals for professionals, some of them are going to include specialized language that will go over the heads of most readers. This is especially true in the health sciences; think about all the crazy medical vocabulary they use on Grey's Anatomy! In short: pick an article you can actually read.

Before you scurry off and start reading that article you just found, you need to slow down and ask yourself whether it's okay to use it for an academic assignment. Just because you approve of the article doesn't mean that your professor will.

Faculty members expect you to use high-quality, trustworthy resources, which is why we're spending all this time teaching you how to use databases instead of sending you off to roam the free web. Your professor might also have specific source requirements for your paper, such as the use of scholarly resources or books.

(And even if your professor didn't care about your sources, it is to your academic advantage to use well-written articles instead of the dubious stuff you find on the web. It's all about high standards, people.)

Here's the good news: if you found your article using a library database, you can be 99.999% sure that it contains factual, trustworthy information. Subscription databases like Academic Search Premier only contain items that have been published in reputable journals, magazines, and newspapers. (You won't find content from a tabloid like The National Inquirer in these library databases!)

That said, you need to think for yourself and verify that your article makes the grade in an academic setting. This goes double if you found the article using Google instead of a database.

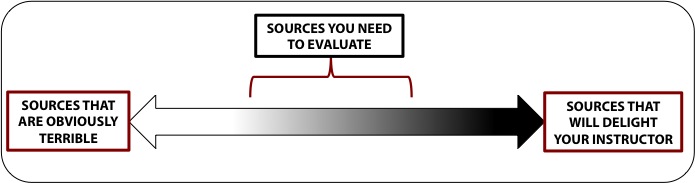

There are sources that are obviously okay (peer-reviewed articles from scholarly journals) and sources that are obviously bad (anonymous web pages that appear to have been written by preschoolers and/or monkeys). It's the stuff in the middle -- the gray areas -- that you need to evaluate.

Librarians and teachers have come up with many, many, many checklists you can use to evaluate both print and online information sources.

Why so many? Because evaluation is subjective, and there's more than one way to do it. It's not about finding a right answer or following detailed, step-by-step instructions. It's about learning to ask yourself questions about what's in front of you, and using your intellect and gut instinct to decide whether your source is trustworthy or kind of shady.

But it will take time to develop that gut instinct, so in the meantime, here are some criteria to consider as you evaluate an article, book, or other information resources.

Ask Yourself:

How Do I Know?

Ask Yourself:

How Do I Know?

Ask Yourself:

How Do I Know?

Ask Yourself:

How Do I Know?